Why Latvia is swapping cheap woodchip for expensive gas

The logical consequence of the increase in the prices of natural gas and petroleum products would be a ban on the export of fuelwood from Latvia, or wood in general.

The rise in fuelwood prices is nowhere near as rapid as the rise in natural gas prices. According to information published by Gaso, the company supplying natural gas to Latvia, gas prices on the stock exchange have risen from €13.84 per megawatt-hour in December 2020 to €81.11 per megawatt-hour in December this year. Arithmetically, this corresponds to an increase of almost six times. In recent months, gas prices have been fluctuating around the same level. This November's price was 6.5 times higher than last November's. Information given to Neatkarīgā by Rīgas Siltums, that the price of wood chips has increased by 30-40% compared to the end of last year, allows us to compare the price increase of natural gas and fuelwood. Of course, this is also a lot, but it is still much less than six times.

The increase in the price of Latvian imported energy resources draws attention to the fact that Latvia is also a large exporter of energy resources in the form of fuelwood. The latest figures published by the Central Statistical Bureau and the Ministry of Agriculture show that between January and October this year, 4.1 million cubic meters of fuelwood were exported from the country, which generated €446 million. Compared to the first 10 months of last year, the monetary gain is up 15.1%, but the increase in the price of wood is still negligible, as the lion's share of the increase in export earnings is due to a 13.3% increase in export volumes. It should be pointed out immediately, however, that in October the increases in gas and oil prices were not yet as huge as in the last few months. Moreover, the October transactions took place even earlier in the execution of contracts. However, the price gap between fossil and wood energy prices had already begun to widen. The question is who will have the mind, courage and strength to close it and in which direction. Will Latvian timber traders be able to afford to charge foreign customers six times the price they were charging before, if only because they have to pay six times the price for fossil energy resources, without which it is impossible to cut down forests and prepare timber for sale? If not, then the export of timber from Latvia should be restricted or banned altogether.

Restricting exports is nothing new. With regard to timber in Latvia, it has been discussed more than once that log exports should be restricted. Forest owners sometimes suspected that the Latvian State was doing this in a bashful way, restricting exports as if to prevent the spread of wood-damaging bugs. Russia, less burdened with international obligations, came to the log export ban officially, but questions remain as to whether such a ban is actually being circumvented by classifying timber in a way that does not comply with the ban.

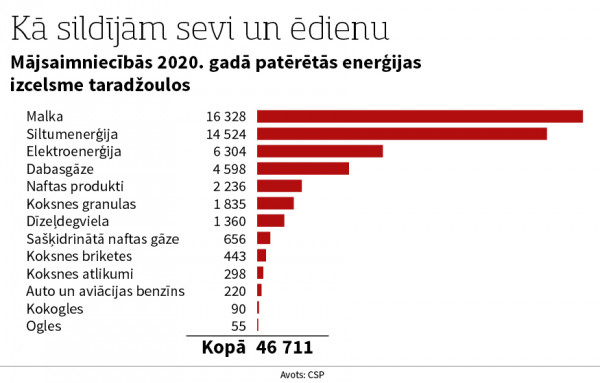

It would now be relevant to retain fuelwood in Latvia in the form of firewood, wood chips, pellets, briquettes, and wood residues. It would be safer to keep all wood in the country because in an energy crisis the prospects for converting, say, wood into furniture would not be very good anyway.

In reality, however, Latvia faces technical, financial and legal obstacles to leaving domestic wood in the country as a fuel of local origin. Latvia has successfully gotten rid of coal-fired furnaces since independence, but there is no way of getting wood into natural gas-fired furnaces. The installation of woodchip furnaces has been going on for 10-15 years, but got entangled in the machinations of the mandatory procurement component (OIK) and was put on hold. The current energy commodity price relationship would ask for only woodchip and other wood furnaces, but these take years to install, not months. It is also not clear what will happen in the next few years. Perhaps a price relationship at a higher price level that is less satisfactory to all parties will be found, or perhaps solutions will be sought through political re-alignment or even wars.

Until the future is known for sure, everyone clings to the cash flows they have already received. Latvia, for example, has received more than €3 billion from its timber exports in the first 10 months of this year, not counting how the economy and the national budget have been underpinned by the local consumption of timber. The direct benefit to the country from these billions is the dividend payments by the state-owned JSC Latvijas Valsts Meži, but the overall benefits to the country are much greater. Latvijas Valsts Meži and private companies in the forestry and timber pay taxes, give jobs, and order from other companies. Latvia also benefits from its place in the timber trade between countries. For example, last year Latvia imported 424,000 tons of wood pellets, according to official data, which is less than a fifth of the 2.3 million tons of wood pellets exported. At least in the short term, the country should expect to lose out not only from wood exports, but also from limiting imports of fossil energy.

Even a brief overview of Latvia's involvement in the international energy chain shows how multifaceted and unalterable by simple decisions this involvement is. That is why the government of Krišjānis Kariņš avoids decisions as much as possible and hopes that the money given to Latvia under the pretext of Covid-19 will allow it to avoid the collapse of the heat and electricity supply systems at least this winter.

*****

Be the first to read interesting news from Latvia and the world by joining our Telegram and Signal channels.