A shocking map shows what we stubbornly refuse to admit - austerity doesn't pay

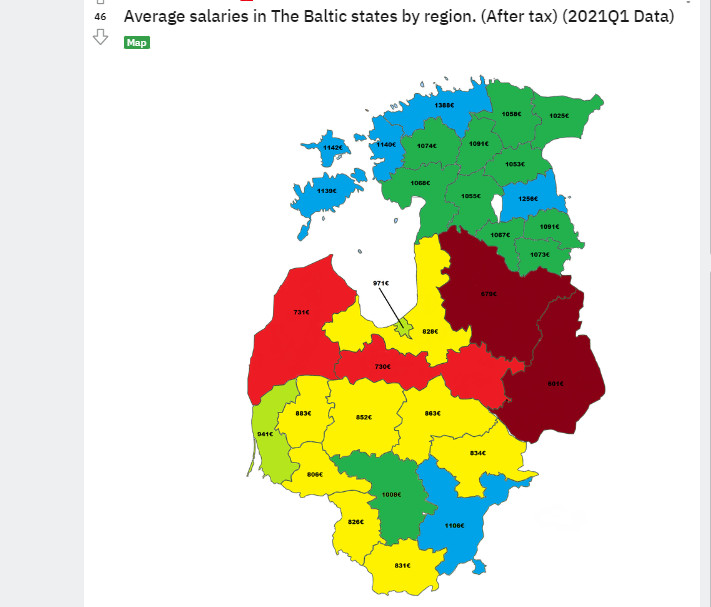

A map showing the differences in salaries (after taxes) between different regions of the Baltic States has shocked some people in Latvia.

Although for years people have been talking about Latvia's growing gap with its two Baltic neighbors, this talk has somehow been relegated to the periphery of perception and subtly placed in the "it's not good manners to talk like that" category. There is even a rather mocking hashtag for such speeches - #everythingisbad.

In other words, if you point out that something is not quite right in our public administration, you are not "right", because it is only Gobzems and his ilk who criticize the state. The "right" thing to do is to support Kariņš and his government and say, "But who else could do it?". I am not drawing any parallels with some of our other neighbors, because their leaders are indeed very different from ours, but that does not mean that the slogan “but who else could do it” therefore becomes any less harmful to the healthy development of society.

As we can see from the map, salary levels in Latvia's richest region - Riga - are lower than in Estonia's poorest rural regions. The comparison with Lithuania does not seem to be so devastating, but only in a way, which will be discussed a little later. The Vilnius and Kaunas regions are ahead of Riga, while the Klaipėda region is on a par with Riga. The other rural regions of Lithuania, on the other hand, are on a par with Latvia's Pierīga region. The rest of Latvia is lagging behind by far.

Now about that “in a way”. The map shows salaries in actual nominal terms, not in real purchasing power. People who frequently visit neighboring countries will have noticed that prices are higher in Estonia and lower in Lithuania (at least a short while ago). These price differences may not be the case for all goods and services, but the overall trend is exactly the same.

Eurostat does not give GDP data by purchasing power parity by region, but by country. In Estonia, GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in 2020 was €24,991; in Latvia, €21,076; in Lithuania, €25,288. As we can see, Lithuania, with its average wage levels but the lowest prices in purchasing power parity terms, is currently the most wealthy Baltic country, while Latvia is already quite far behind.

People have been asking questions for years about the causes of this lagging. A very typical tweet is made by Alberts Ziemelis: "Even Lithuania, which until 2005 was steadily falling behind Latvia, has overtaken us. Is this a consequence of Kremlin agents in the Latvian elites?"

This entry reflects all our fantasies and delusions like a drop of water. Firstly, a large part of Latvians since the time of the Ulmanis rule still lives in the belief that Lithuania is "lagging behind". In fact, in 2005 Lithuania had already passed Latvia by. Not as much as now, but to say that Lithuania was "steadily falling behind" in 2005 is only a reflection of our own imaginations. Secondly, the unshakeable belief that we are being pulled back by some mysterious forces - "Kremlin agents in the Latvian elites". These mysterious forces may be unconnected with the Kremlin, but it is "they" who are to blame. It is not us who are to blame, but them (everyone can make up his own "they").

What determines the level of prosperity of countries? There are different theories, but with different variations they come down to two basic factors. These are the quality composition of the population and the course of political leadership. Because the quality composition of the population sounds too politically incorrect, the concept is often replaced by historical conditionality. This is understood as the general level of civilization of a society: education, culture, living habits, traditions, norms of behavior, etc. It is unlikely that any country that is currently lagging far behind could rapidly reach the level of Luxembourg if it were to be led by a Luxembourg government. It is just that much of what works in Luxembourg would not work there.

There are few examples in the world history of once backward countries becoming leaders in prosperity. Norway, Korea, Ireland, Singapore, to name a few. Mostly all countries, by and large, are now where they were, say, a hundred years ago.

This is also true of Latvia, and we should not fool ourselves with dubious statistics which “show” that Latvia in 1938 was almost on a par with Western Europe. It is enough to compare the number of cars per capita, the use of household appliances (washing machines, gas/electric stoves, fridges, etc.), the level of rural mechanization (tractor/horse ratio) and electricity consumption to throw these "statistics" into a wastebasket.

Fortunately, a set of "historical habits" is not the only determinant of well-being. The political course of the government is no less important. Both Singapore and Korea became wealthy states thanks to tough reforms implemented in a less than democratic way. Norway's rapid rise was largely due to its rich oil deposits. Ireland is the only country to have made a giant leap in literally ten years (1995-2005), overtaking previously richer countries. Unfortunately, Ireland can also serve as little of an example for us, because Ireland in many ways encouraged an influx of labor from outside that would not be accepted by the Latvian public.

However, in our case, the talk of reaching Sweden's level, which was popular in the early 1990s, has long been obsolete. Now we need to talk about how to keep up with Lithuania. There is a growing realization that the current economic policy has exhausted itself and needs to be changed urgently. That is to say, it is not "Kremlin agents in the political elites" but the economic policies of governments that have brought us to our current state of backwardness.

Latvia made a fatal mistake in the method it chose to deal with the 2008 crisis. There is not a single serious economic study at the world level that has put what Latvia did in a positive light. At the same time, there has been no critical evaluation of this method in Latvia. Since 2009, the country's economic course has been determined by the same forces that supported the methods that led to a very rapid, unamortized economic decrease. As a result, Latvia lost up to 200,000 people of working and fertile age. It could be argued that fewer people left Lithuania, and that the economic crisis there was dealt with in a similar way, but Lithuania, having overcome a severe crisis, learnt from its mistakes and gradually abandoned its very conservative economic policy, which can be described in one word as “austerity”.

While the ruling political forces in Latvia were prepared to go as far as ignoring their own laws in order not to donate a paltry €60 million to the medical profession in 2019 (now, after the Covid-19 money rain, this sum, which then they were too stingy to pay, looks pitiful), the Lithuanian government was not afraid to raise the minimum wage rapidly and regularly. In 2021 to €642, in 2022 to €730. I remind you that as recently as 2015, the minimum wage in Latvia was €360 and in Lithuania €300. While Latvia continued to keep people starving, Lithuania abandoned this policy and has now broken through to the top of the Baltics.

I am not saying that this minimum wage increase is the decisive factor in Lithuania's growth. Absolutely not. It is just an indicator of a change in the overall course. The masochistic belief that austerity and saving every penny will bring prosperity in the end does not work in macroeconomics (nor in microeconomics). But investing in people - in education, medicine and elsewhere, including salaries - works. Austerity does not pay. Not in everyday life, not in the economy as a whole.

*****

Be the first to read interesting news from Latvia and the world by joining our Telegram and Signal channels.